It can be unclear how rent prices and vacancy rates for multifamily real estate react to changes in the overall U.S. economy, specifically in relation to the job market. A struggling economy marked by low wages and high unemployment makes on-time rent payments more difficult for tenants. It also results in declining household formations and absorption as those hit hardest move out of their apartments and in with friends or family.

A reduction in demand for apartments caused by this type of situation typically forces rents to stagnate while vacancies rise. Alternatively, the uncertainty that comes with a slack job market may lead would-be homebuyers to remain in their apartments a bit longer while waiting for the doubt to clear and the economy to recover. This has a countervailing effect that could prop up the multifamily-housing sector even in poor macroeconomic conditions.

With these opposing forces in mind, looking at permanent unemployment trends is a good starting place to determine the potential timing and magnitude of stress in the multifamily sector. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics defines permanent unemployment as jobs that are terminated involuntarily and are not expected to return in the next six months.

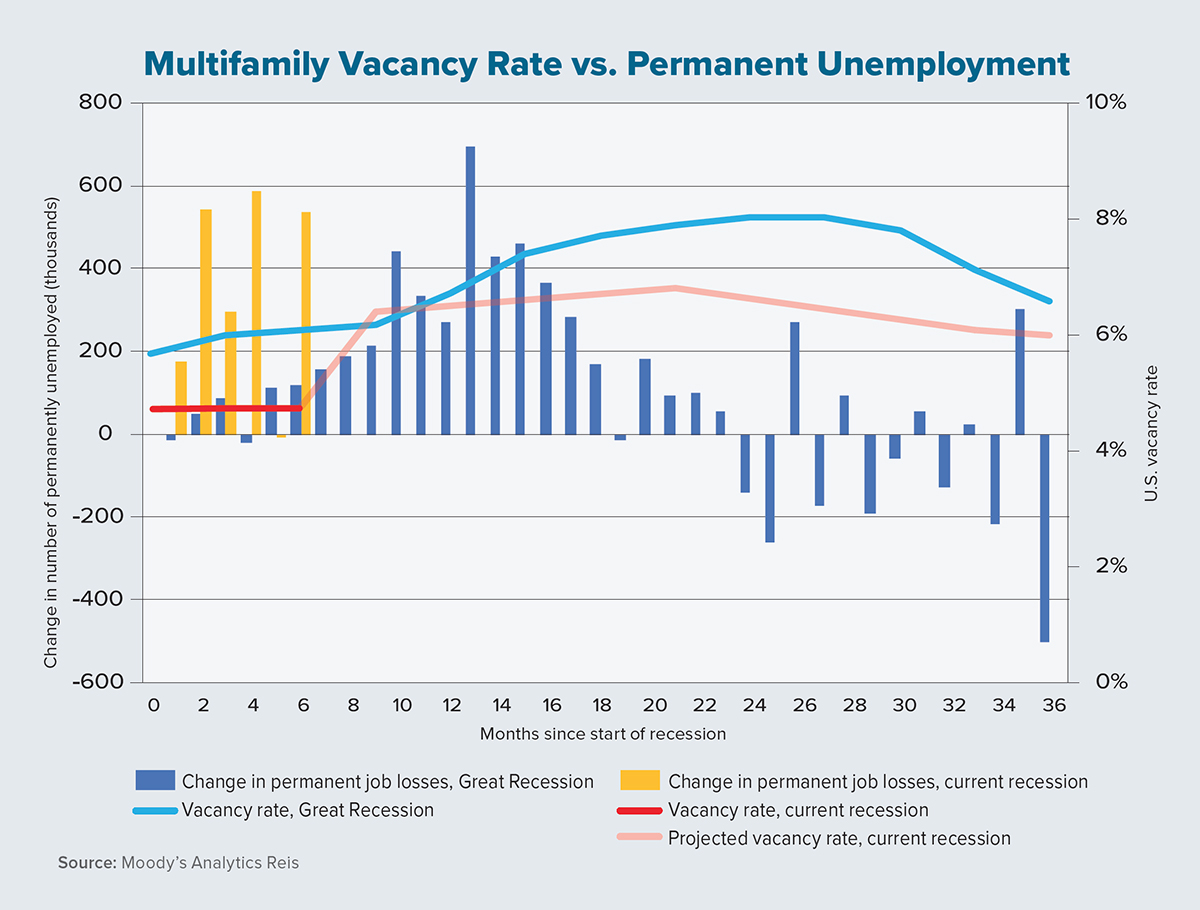

The chart on this page highlights the relationship between permanent unemployment and multifamily-housing outcomes during the Great Recession of 2008-2010 and the current recession related to COVID-19. It’s immediately clear that there are varying paces of permanent job losses during these two periods.

It took nearly nine months for monthly job losses during the Great Recession to show a significant increase. In contrast, during the ongoing pandemic, large numbers of permanent job losses began almost immediately and the levels stayed elevated through this past August, a month in which more than half a million Americans entered the ranks of the permanently unemployed.

For all the rhetoric related to multifamily being mostly spared during the Great Recession, the national vacancy rate peaked nearly 250 basis points higher than its year-end 2007 level of 5.7%. Interestingly (as shown on the chart), the peak vacancy rate of 8% occurred roughly 26 months into the Great Recession, much later than when the bulk of permanent job losses occurred in months nine to 17. Looking forward to the recovery, the vacancy rate lagged and didn’t begin to drop until well after the number of permanently employed began declining (illustrated by negative changes on the chart).

How does this relationship differ during the current pandemic-fueled recession? First and foremost, the job losses came more quickly and in much larger magnitudes compared to the Great Recession. During the first six months of this downturn, three months saw permanent job losses of more than 500,000. This level of job losses occurred only once during the Great Recession.

Second, the vacancy rate during the current recession was completely flat over the first six months even as employment suffered mightily. This is different from the prior recession when the vacancy rate began rising during the worst of the job losses.

By year-end 2020, Moody’s Analytics Reis expects the U.S. multifamily vacancy rate to spike at 6.1% as the surge in permanent unemployment in recent months creates consequences. Furthermore, we expect the vacancy rate to remain elevated for the next few years as the job market sorts itself out. As shown during the Great Recession, multifamily-sector recovery tends to lag behind job-market stabilization.

Lastly, permanent job losses often result in workers who find new careers in new industries and, sometimes, in new locations. It will be fascinating to follow migration patterns over the next few years in relation to this pandemic. These shifts will surely impact multifamily markets at the metro level. ●

Authors

-

Thomas LaSalvia, Ph.D., is senior economist at Moody’s Analytics Reis. He has extensive experience in urban economics and credit risk.

View all posts -

Barbara Byrne Denham is former senior economist and associate director at Moody’s Analytics. She previously served as chief economist at Eastern Consolidated and is a Ph.D. candidate at New York University, where she has studied economics, monetary theory and game theory.

View all posts