While business leaders continue to evaluate their future office- space requirements, an emerging discussion regarding a “flight to quality” has gained attention within commercial real estate circles. Anecdotally, there are instances where companies have declined to renew space in an older Class B or C property, only to move to a new and shiny “trophy” property in another part of town.

But do these anecdotes amount to enough one-way activity to move the needle on space and capital-market performance metrics between property classes? At this point, the data supports a resounding “no.” In fact, a combination of national- and metropolitan-level statistics reveal that, on average, Class B and C properties are slightly outperforming their Class A counterparts. This doesn’t mean that trading up is not occurring, but it’s more likely that the true level of this activity is out of touch with the rhetoric.

So, what are the relevant arguments for the flight to quality? First, many office-using companies have done quite well throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Greater profits, higher stock prices and an expectation of further growth are not uncommon, especially among many large office-using firms. Combining this business performance with the potential for rent concessions or discounts within certain markets, and decisionmakers may think that now is the right time to trade up.

Second, the labor market is quite tight and many workers may have become emboldened to request less time at the office, or are even willing to quit if they do not get their desired flexibility. Even if this threat isn’t credible, companies will have to compete for workers and entice them to the office if that is what business leaders deem necessary. Class A space may be required to gain access to the best and brightest talent.

Lastly, in a post-pandemic, office-using world, office time will likely be used for collaboration and team building. This tends to require open and naturally lit space with more amenities.

Each of these arguments are economically sound, but there also are counterarguments. Some business leaders may have more of a suburban mindset, making an effort to be closer to where many of their homeowning employees have chosen to place roots. Other companies may have no need or desire for Class A space. It’s also possible that some risk-adverse firms are still uncertain at this point about their future office needs and are thus unwilling to take the plunge into new Class A space. But what does the data tell us?

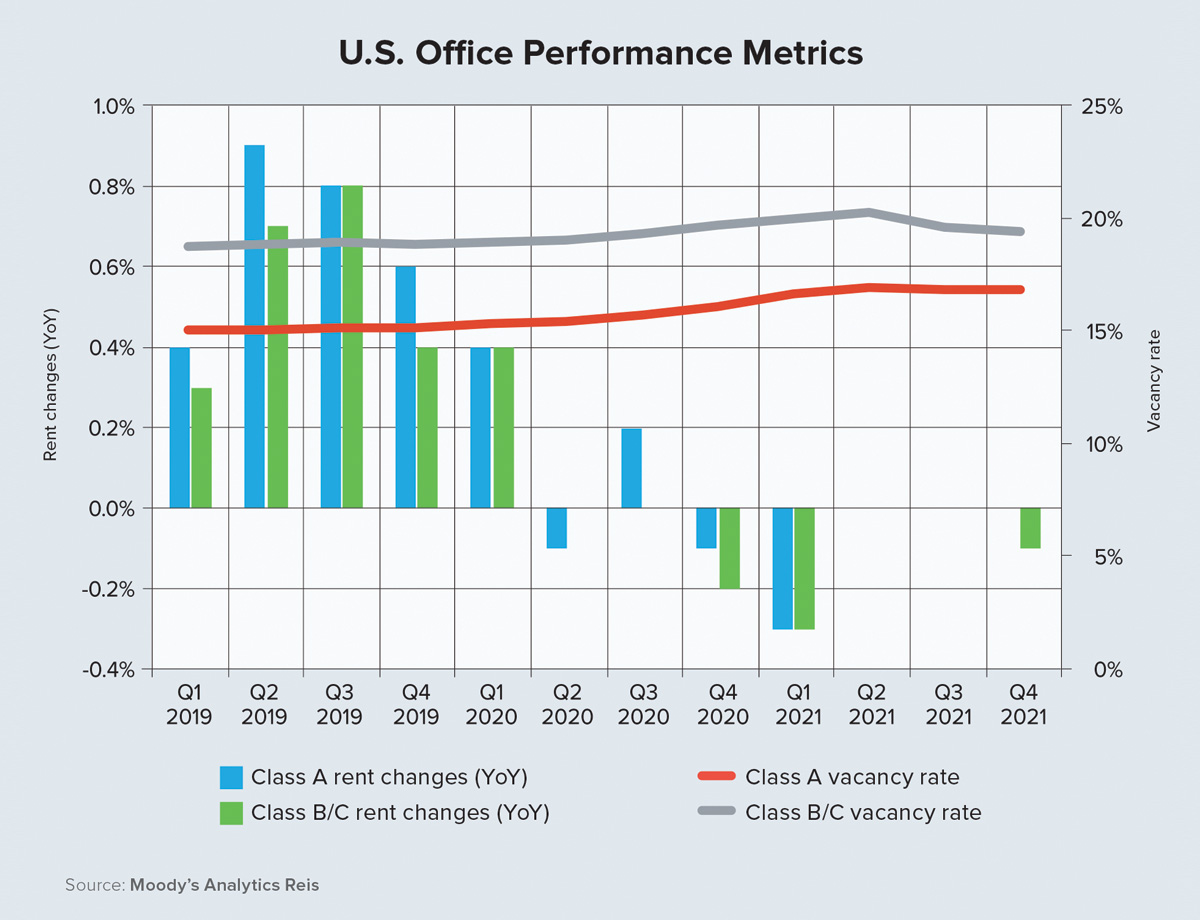

Separating performance metrics for both capital- and space-market activity shows that any flight to quality between asset classes remains relatively minor. Focusing on space-market performance, the chart on this page illustrates that very little differences exist for pandemic-era performance between Class A and B/C properties.

To help determine how robust the national- level figures are, we performed a metro-level analysis using simple differences between class performances. For each class of office property, we calculated the difference in the vacancy rate from 2019 through 2021, then calculated the differences between these class-specific vacancy-rate changes.

Of our 82 primary office-sector metros, only 24 had situations where Class A assets were outperforming B/C assets. Of these 24, only a handful were substantial outperformers, and an even smaller list had a significant decline in the Class A vacancy rate. The top of this list includes Greenville, South Carolina; Rochester, New York; Cincinnati; and Greensboro, North Carolina.

To conclude, the flight-to-quality trend has its merits in the post-pandemic world, and some businesses will find it worthwhile to trade up. As of now, however, the data does not support a widespread proliferation of this phenomenon, at least as it amounts to the performance of Class B/C versus Class A properties.

If trading up is occurring in substantial numbers, it is likely occurring within the same asset class and not between classes, which is something beyond the scope of this analysis. Changing buildings for better natural light, a slightly better view or space that is more environmentally friendly is likely. It is on the margins where this phenomenon may truly lie. ●

-

Thomas LaSalvia, Ph.D., is senior economist at Moody’s Analytics Reis. He has extensive experience in urban economics and credit risk.

View all posts