Although the worst of the COVID-19 health crisis is likely over, the economic fruits of the recovery are unlikely to be shared equally. Pandemic-induced structural change is evident.

How and where we work has shifted. Lingering job losses have — and will continue to — disproportionately hurt lower-income households. This will impact multifamily-housing properties, particularly those in dense urban areas, which felt the brunt of the economic blow during the past year. They will recover, but the journey back to pre-pandemic peaks will be a bit more arduous compared to their suburban counterparts.

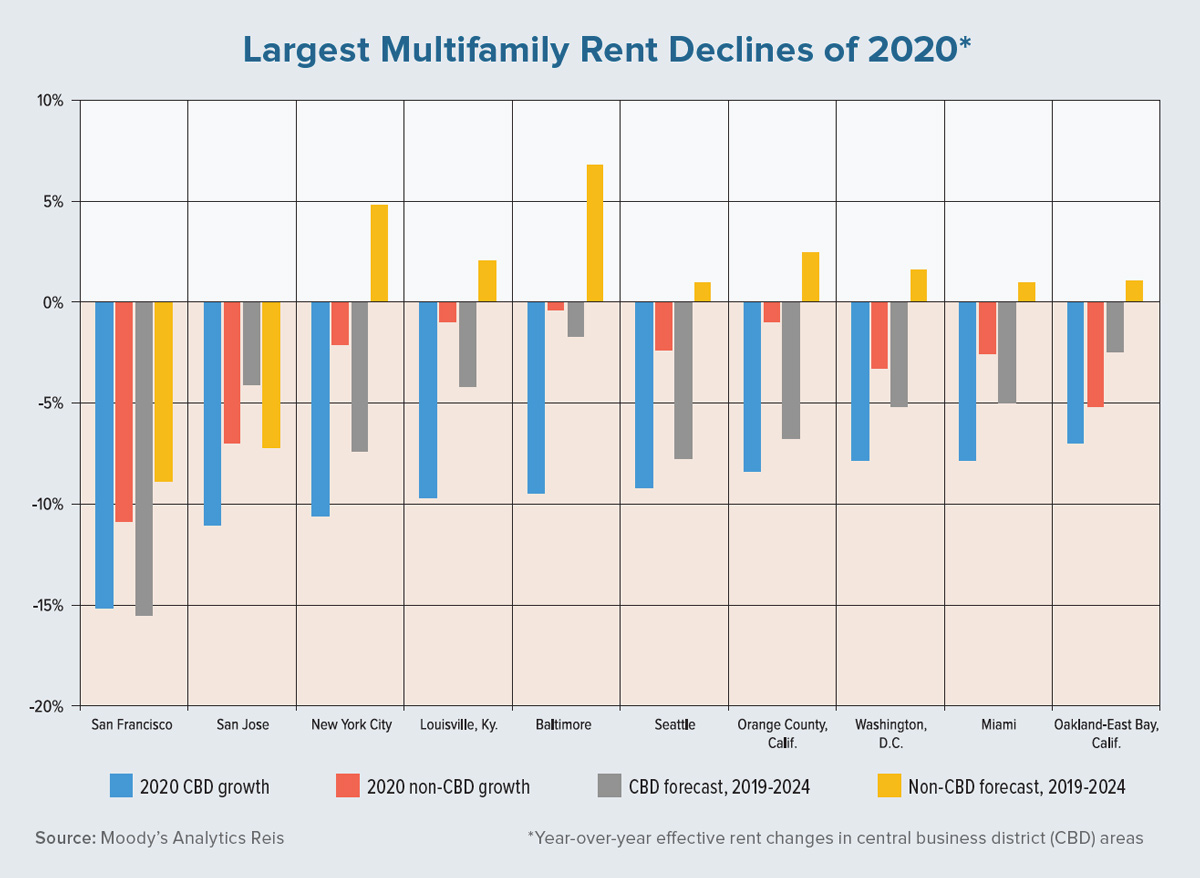

Over the course of 2020, U.S. multifamily effective rents fell by 2.9%, but much of this decline was reserved for urban areas. When comparing effective rents in central business districts (CBDs) to those in non-CBD submarkets, Moody’s Analytics Reis found a difference of 310 basis points, with effective rents falling by 3.6% in CBDs and by 0.5% in non-CBD areas during the past year.

As shown on the accompanying chart, the worst rent performances occurred in some of the most dense CBDs, where COVID-19 infection rates and mandated shutdowns were the most substantial early in the crisis. But the story has more nuance: Historically, CBD rent levels in places such as New York City or San Francisco have been more varied during downturns. In these same markets, apartment supply growth has been robust over the past five years, an important consideration as attention turns to the recovery.

With U.S. gross domestic product growth expected to climb above 5% this year and next, multifamily demand drivers are poised to bounce back, and the sector is likely to begin growing again later this year. But there still are headwinds to face, depending on the asset class and location.

First, the economic effects of the pandemic have disproportionately hurt lower-income households. Although the nation is far from its peak unemployment rate of nearly 15% early in the crisis, as of this past February there were still 4.3 million more unemployed individuals versus a year earlier prior to the pandemic.

We expect hiring to pick up dramatically in second-quarter 2021, but the structural changes will keep so-called “long-term” unemployment stubbornly high. Studies show that the longer a person remains unemployed, the more their skills deteriorate and the less likely they are to be hired for a new job. This is likely to put pressure on Class B and C apartment fundamentals in both urban and lower-income suburban locations.

Second, the robust urban supply growth of apartments prior to and throughout the pandemic is likely to continue over the next few years as many projects have “left the station.” From 2015 through 2019, U.S. multifamily completions averaged 238,000 units per year for an average annual growth rate of 2.1% during this period, according to a Moody’s analysis of properties with 20 or more units.

Much of this growth was in and around blossoming urban areas. And while overall apartment inventory growth slowed in 2020, the growth of completions in CBDs remained above 3% for the year. With many urban projects delayed but not canceled due to temporary shutdowns in certain locations, we expect supply growth in 2021 to remain strong.

Third, downward demand pressures are likely to continue in the most-expensive urban areas. While details regarding the return to the office are still being worked out, some households will have greater freedom to choose where they live. This will prompt some to seek rent savings through a permanent move. Although we do not support a long-term “death to density” sentiment, the Bay Area, New York City and other high-rent areas were due for outward migration as the cost of housing became a burden for many tenants.

The data is clear: Dense urban areas have felt more economic effects of the pandemic and their recovery will be unbalanced. Supply growth, the emergence of remote work and the consequences of extended unemployment will mean a longer and more arduous journey back to pre-pandemic heights for CBD apartment markets across the country. If and when the recovery is fully realized later this decade, we are likely to see a younger, slightly less-affluent population of urban renters who are excited to experience the various cultural and career pursuits that has attracted previous generations. ●

Author

-

Thomas LaSalvia, Ph.D., is senior economist at Moody’s Analytics Reis. He has extensive experience in urban economics and credit risk.

View all posts